By: David Talbot, Managing Director, Head of Equity Research

Uranium prices are up 52% year-to-date from US$48/lb to US$73/lb U3O8. While its positive performance early in 2023 may be partially attributed to physical uranium purchases, this buying had ceased by April. Only since late September have investment funds resumed physical purchases (~1.8M lbs) as investor sentiment (Sprott Physical Uranium Trust (TSX:U.U, Not Rated) Mark Price to NAV > 0) tested positive territory in late September for the first time in seven months. The reality is that the rising uranium price of late summer leading up to the World Nuclear Association (WNA) symposium was due to the realization that nuclear power is growing at a quicker rate than previously anticipated. This is what we have been waiting for some time…demand is finally driving the sector. Two years ago, things were different. Nuclear reactors were closing, the uranium market was depressed, there was plenty of inventory and mines were closed.

Nuclear continues to supply 10% of global electricity and 25% of carbon-free power, and generating capacity projects are underway in several jurisdictions. Thus, the demand for uranium is growing. This was summed up in the WNA’s bi-annual Nuclear Fuel Report last released on Sept 7, 2023. WNA forecasts that nuclear power capacity is rising at 3.6% annually vs 2.9% outlined in the 2019 report. There are currently 436 operating reactors, with 60 under construction, 110 planned and 321 proposed. WNA’s estimates of uranium requirement for 2023 totals 171M lbs U3O8 vs 128M lbs of production last year. Red Cloud estimates 175M lbs of U3O8 demand and 135M lbs of supply.

There is growing support for nuclear power. WNA’s reference scenario anticipated total power generation of 366 GWe will rise by 87% to 686 GWe by 2040. China is leading the way with anticipated growth of 154 GWe, followed by India at 32 GWe and Japan at 21 GWe. South America, Africa, Russia, Korea, Europe and the USA are each to increase by 7-9 GWe.

We point to a more positive long-term outlook for nuclear power given proactive Government policies, improving public acceptance, nuclear power economics, and climate change impact. More recently, the security of energy supply has also come to the forefront. Specifically, uranium demand is being driven by active reactor construction in many jurisdictions, particularly China (24) and India (8). Several newcomers enter the equation including Ghana, Kenya, Poland, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Uganda and Uzbekistan. This is doing more than offsetting demand from countries that are terminating use such as Armenia, Belgium, Taiwan, and Spain. Furthermore, there have been numerous power plant extensions, taking plant life from 60 to 80 years, therefore delaying shutdowns. Small modular reactors are also entering into the mix. The trend of physical uranium purchases, while not as strong as 2021-22, continues, and these purchases have also been added to the demand for the first time.

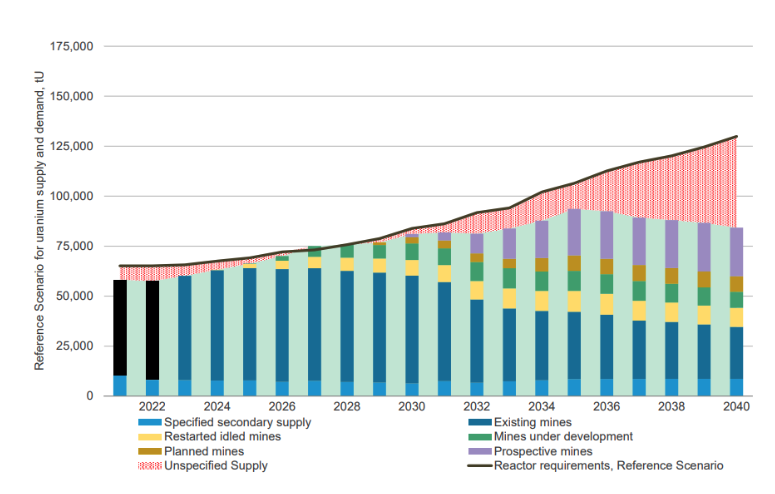

Uranium supply, perhaps incorrectly, wasn’t the main theme of the 2023 WNA Nuclear Fuel Report. Most excitement was centred on the expectation that nuclear power capacity was growing at 3.6% annually rather than at 2.9% as previously thought. Pending uranium supply gaps seemed to be treated as secondary, if not downplayed. The ample resources outlined in the NEA/IAEA Uranium Resources, Production and Demand report, formerly known as the Red Book (link), was noted during a WNA presentation as being the basis for future mine supply. We concur that uranium may not be rare but getting it out of the ground is an entirely different matter. Plus, most of the resources stated in the Red Book are certainly not anything close to being NI-43-101 or JORC compliant. The WNA study does outline “specified supply” that includes known secondary supply, uranium mines, mine restarts, development projects, and potential future planned and prospective mines. WNA was quick to note that part of future uranium supplies cannot be predicted with any degree of certainty. The WNA includes “unspecified supply” within its methodology from somewhat iffy sources such as commercial inventories, unspecified secondary supply, project expansions and other potential supplies. In essence, WNA says it doesn’t know what to call this supply, but it’s still supply. Calling this supply of any kind, when no supply really exists, in our opinion, minimizes the message that a rapidly emerging supply-demand gap is looming.

Covid-19 impacted uranium production, falling by 25%, before rebounding by 10% in 2021. That said, production only rose 3% between 2020 and 2022, despite higher uranium prices. And the only two producing countries that increased output were Canada and Kazakhstan on the bank of restarts and resumed production. Last year just 75% of reactor requirements were covered by primary production. The top seven countries produced 94% of all uranium….and a declining number of countries would be considered safe zones or friendly to the west (perhaps only Canada, USA, Australia and Niger).

WNA’s Reference scenario for uranium supply and demand.

Source: World Nuclear Association Nuclear Fuel Report 2023

WNA suggests that secondary supply is expected to decrease from 12% of total record demand in 2023 to 8% by 2040. Recycling and MOX will become more important. Underfeeding and tails re-enrichment will gradually decline considering increased enrichment of natural uranium will be needed. WNA notes that underfeeding may decline 1.3M lbs to 3.9M lbs. Uranium inventories at nuclear utilities have been dropping since 2018, from about 150M lbs to 130M lbs. Meanwhile, investment funds have been purchasing material, adding about 20M lbs in 2021 and 2022.

WNA’s fuel balance shows the need for additional uranium through 2025 and this could be part of the reason that we see rising uranium prices currently. While anticipated supplies should provide for expected demand during the 2026 to 2028 period, by 2029 we are back in a uranium supply deficit as supplies fall off dramatically. While there may be enough uranium in the ground, I was quite surprised for the WNA to conclude its presentation strongly in favour of the need for additional supply sources, and that there should be cooperation between uranium suppliers and nuclear utilities. Uranium miners need incentives to develop new mines, accelerate new development and make discoveries, and failing that, not all nuclear utilities will receive the uranium that they need to keep their reactors in operation.

Positive trends are clearly visible. Nuclear capacity growth is higher than anticipated. We are seeing a strong recovery in the uranium market. And while there are ample uranium resources, incentive is needed to help with the rapid development of uranium projects required in the near- to mid-term.